The Great Emu War

Australia's Surrender on December 10, 1932

The Great Emu War was an unusual military operation in Australia during November and December 1932. It involved soldiers trying to control a large group of emus that were damaging wheat farms in Western Australia. Despite using machine guns, the effort didn’t succeed, and the emus continued to cause problems while the army used up a lot of ammunition.

Background

After World War I, the Australian government gave land in Western Australia to more than 5,000 returning soldiers to start farms. Many of these men had no farming experience, and the land was poor for growing crops. A long drought reduced rainfall by about 40%, which made farming even harder. Then the Great Depression caused wheat prices to drop 30% in 1930, and unemployment rose to 30%. The government encouraged more wheat production but failed to provide promised financial help, leaving farmers struggling.

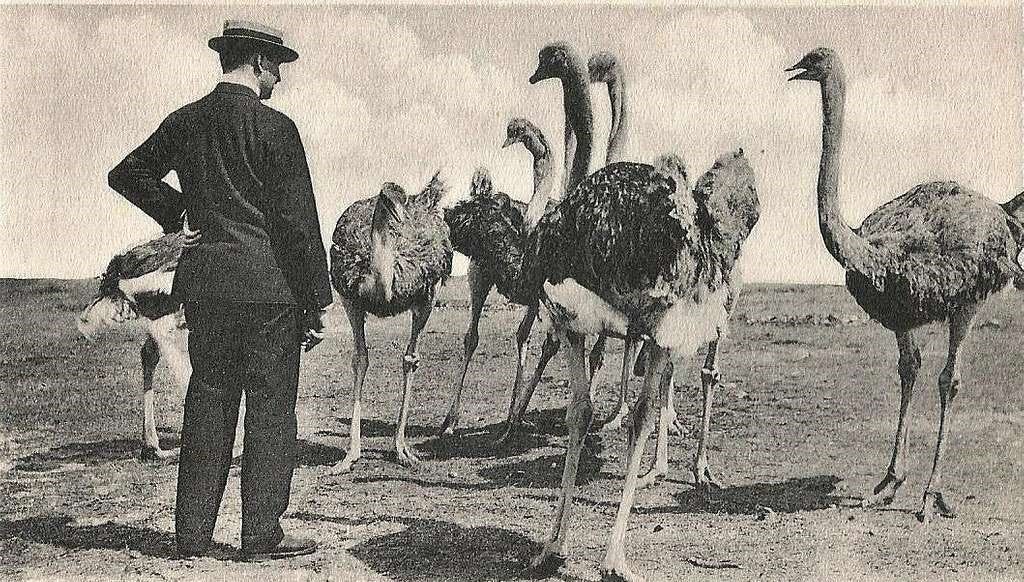

In late 1932, rain finally came, and around 20,000 emus moved from dry inland areas to the farms near the coast for food and water. The emus ate and trampled the wheat crops…one farmer lost 3,000 acres.

Starting the Operation

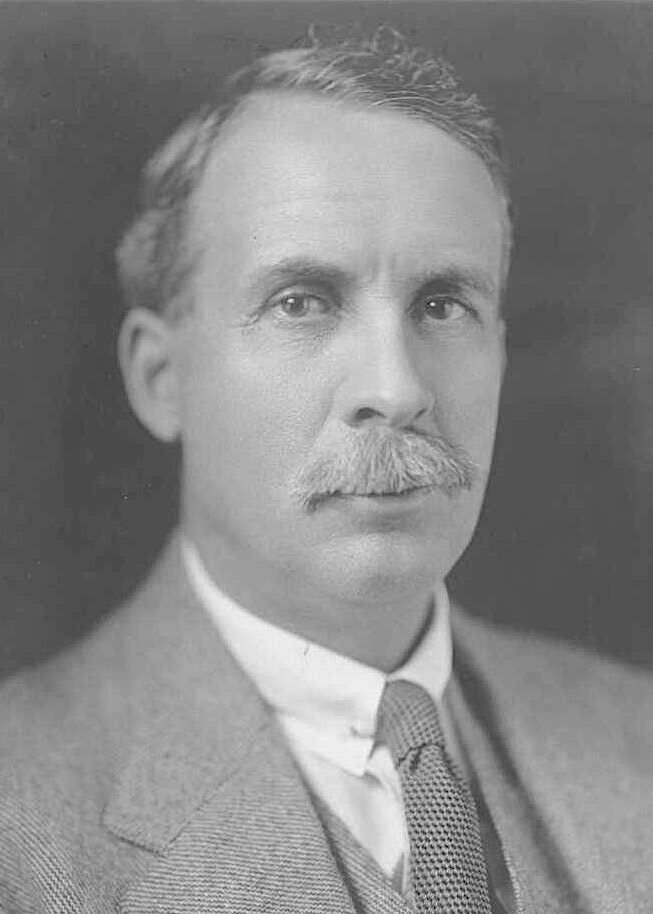

Having been in the war, the farmers knew machine guns worked well against groups in battle. Their own guns weren’t effective against the fast emus, so they asked the Minister for Defence, Sir George Pearce, for army help. Pearce agreed, seeing it as training for soldiers and a way to support the veterans. The state paid for transport, farmers covered food, lodging, and ammunition, and a filmmaker came to record it.

What Happened in the Campaign

The operation started on November 2, 1932, led by Major G.P.W. Meredith with two soldiers, two Lewis machine guns, and 10,000 rounds of ammunition. Early attempts to gather the emus for shooting failed because the birds split into small groups and ran away. On November 4, they tried an ambush at a dam where over 1,000 emus gathered, but the gun jammed after killing just 12, and the rest escaped.

The emus quickly learned to adapt: they used lookouts to spot danger and broke into smaller groups, like guerrilla fighters. Trying to chase them with guns on trucks didn’t work as the terrain was rough, and emus could run 30 to 50 mph. On November 8, politicians in parliament made fun of the failure, leading to a short pause.

The effort started again on November 13 with better plans, using local farmers to help set up ambushes. They killed about 100 emus a week until December 10, when the major was called back. In total, they confirmed 986 kills using 9,860 bullets, and claimed another 2,500 died from wounds later (though historians doubt that number).

The emus were tough…some survived multiple shots and kept running. My favorite quote about the event came from Major Meredith, who said,

“If we had a military division with the bullet-carrying capacity of these birds, it would face any army in the world ... They can face machine guns with the invulnerability of tanks. They are like Zulus whom even dum dum bullets could not stop.”

After the War

The army refused later requests for help in 1934, 1943, and 1948. Instead, paying bounties to hunters worked better: in the first six months of 1934, 57,034 emus were killed. From 1945 to 1960, over 284,000 were taken out.

Newspapers in Australia and abroad mocked the operation as a big failure. Pearce was called the “Minister for the Emu War.” Today, December 10th, is when Australia withdrew from the war, and it is now jokingly referred to as the day they surrendered.