Sir Walter Raleigh’s Execution: Politics and Justice in Jacobean England

October 29, 1618 – Westminster

The End of an Elizabethan Figure

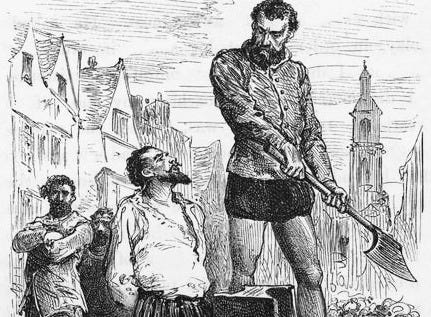

On October 29, 1618, Sir Walter Raleigh was executed at Westminster’s Old Palace Yard. The 65-year-old statesman and scholar approached the scaffold wearing formal black velvet and silk stockings, notably retaining a diamond ring given to him by Queen Elizabeth I. His composed bearing and memorable last words to the hesitant executioner—”What dost thou fear? Strike, man, strike!”—would become part of English historical tradition.

This execution represented the culmination of complex political circumstances dating back to 1603. King James I’s decision to enforce a long-suspended death sentence was significantly influenced by Spanish diplomatic pressure and his pursuit of a dynastic marriage alliance. The event would have lasting implications for public perception of Stuart governance and Anglo-Spanish relations.

Raleigh’s Rise Under Elizabeth I

Walter Raleigh, born circa 1552-1554 into Devon’s Protestant gentry, began his career through military service in the French Wars of Religion and Ireland’s Second Desmond Rebellion (1580-1583). His effectiveness during the Irish campaign, particularly at Smerwick Fort, brought him to royal attention.

Between 1583 and 1585, Raleigh experienced remarkable advancement at court. Queen Elizabeth granted him a knighthood in January 1585, followed by appointments as Lord and Governor of Virginia, Lord Warden of the Stannaries, and Lord Lieutenant of Cornwall—making him the first commoner to hold this latter position. By 1587, he had attained the prestigious post of Captain of the Queen’s Guard. These offices brought substantial revenues, including the wine monopoly that yielded £1 annually from every vintner in England.

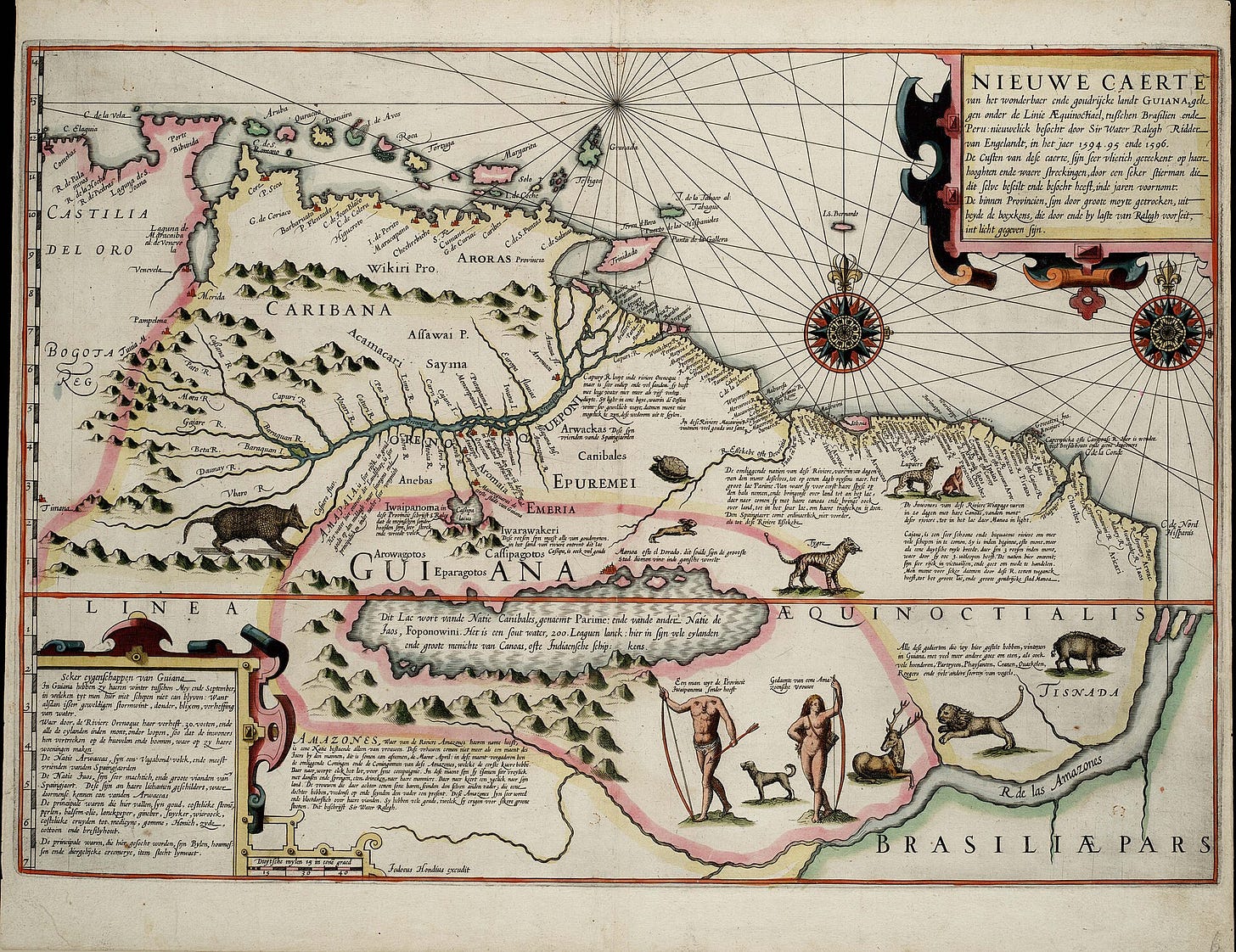

Raleigh’s contributions to Elizabethan England were substantial: He sponsored the voyages that established English claims to Virginia (1584-1587), participated in the defense against the Spanish Armada (1588), and later produced “The History of the World” (1614), a scholarly work exceeding one million words that would influence English historical writing for generations.

His rapid elevation and accumulated wealth, however, created tensions at court. Contemporary observers noted his prideful demeanor, which would later contribute to his political isolation.

The 1603 Trial and Its Implications

James I’s accession in March 1603 fundamentally altered Raleigh’s position. The new king prioritized peace with Spain, while Raleigh represented the previous reign’s anti-Spanish policies. By July 1603, Raleigh faced charges of participating in the “Main Plot,” allegedly aimed at replacing James with Lady Arabella Stuart.

The Winchester trial of November 17, 1603, has been extensively studied by legal historians as an example of procedural irregularities. The prosecution relied almost entirely on Lord Cobham’s written statement, which implicated Raleigh but was never subjected to cross-examination. Cobham had subsequently retracted his accusations in writing. When Raleigh invoked traditional rights to confront his accuser, citing both biblical precedent and Edwardian statutes, the court denied these requests.

Attorney General Sir Edward Coke’s prosecutorial approach employed notably aggressive rhetoric, describing Raleigh as “a spider of hell” among other epithets. The jury deliberated for approximately fifteen minutes before returning a guilty verdict. Significantly, contemporary accounts indicate that public sentiment shifted in Raleigh’s favor during the proceedings.

James suspended the execution in December 1603, commuting the sentence to imprisonment.

The Tower Years (1603-1616)

During thirteen years of confinement in the Tower of London, Raleigh maintained quarters appropriate to his social status. His wife Elizabeth resided with him, and their son Carew was born there around 1604-1605. Raleigh utilized his time for intellectual pursuits, maintaining a substantial library, conducting chemical experiments, and cultivating medicinal plants.

His major scholarly achievement was “The History of the World,” a comprehensive chronicle from creation to 130 BC based on sources in six languages. Published in 1614, the work contained observations on governance that Archbishop Abbot deemed sufficiently provocative to warrant temporary suppression. Nevertheless, it achieved widespread readership, with eleven editions printed in the 17th century.

The Fatal Guiana Expedition

In 1616, James released Raleigh to lead an expedition seeking gold deposits in Guiana. Critically, the release did not include a pardon; the 1603 death sentence remained legally active. James imposed strict conditions prohibiting conflict with Spanish interests, while simultaneously sharing Raleigh’s plans with Spanish Ambassador Count Gondomar—a diplomatic gesture that compromised the mission’s prospects.

The 1617 expedition encountered multiple difficulties. Raleigh, too ill to lead the crucial river journey, delegated command to Lawrence Kemys. When Kemys’s force reached the Spanish settlement of Santo Tomé, which blocked access to the alleged gold deposits, fighting erupted. Raleigh’s son Walter died in the initial engagement. After failing to locate gold and burning Santo Tomé, Kemys committed suicide upon returning to Raleigh’s ship.

Diplomatic Pressures and Execution

Despite the expedition’s failure, Raleigh returned to England rather than seeking French exile. Count Gondomar immediately demanded enforcement of the 1603 sentence. James faced considerable pressure: the proposed Spanish Match offered a substantial dowry, and maintaining peaceful relations with Spain remained central to his foreign policy.

Rather than conducting a new trial, James invoked the original 1603 death sentence. The government published a lengthy justification of this decision, though it failed to sway public opinion.

October 29, 1618: The Final Act

On the morning of his execution, Raleigh maintained remarkable composure. After taking breakfast and smoking tobacco, he dressed formally for the occasion. At the scaffold, he delivered a 45-minute address, maintaining his innocence of various charges while acknowledging his sins before God.

When presented with the axe, he examined it and remarked: “This is a sharp Medicine, but it is a Physician for all diseases.” He declined a blindfold, stating: “Think you I fear the shadow of the axe, when I fear not the axe itself?”

The execution required two strokes. Notably, the crowd remained silent rather than offering the traditional acclaim for the king—an indication of public sentiment. Raleigh’s widow Elizabeth received his head, which she reportedly preserved for the remainder of her life.

Historical Assessment

Raleigh’s execution demonstrated the complexities of early Stuart diplomacy and the tensions between Elizabethan and Jacobean political cultures. James’s decision to satisfy Spanish demands by executing a prominent English figure generated significant public disapproval and contributed to growing concerns about foreign influence on English policy.

The case influenced subsequent legal developments regarding confrontation rights and procedural fairness. More immediately, it revealed the limitations of James’s diplomatic strategy. The Spanish Match, for which Raleigh was arguably sacrificed, ultimately failed when Prince Charles returned from Madrid unmarried in 1623.

Raleigh’s transformation from controversial courtier to Protestant martyr illustrates how political executions could produce unintended consequences. His scholarly works, particularly “The History of the World,” ensured his intellectual legacy, while his composed death reinforced his rehabilitation in public memory.

The execution marked a definitive end to the Elizabethan era’s expansionist, anti-Spanish orientation, replaced by James’s vision of diplomatic accommodation. This shift would continue to generate tensions throughout the early Stuart period, contributing to the constitutional conflicts that would emerge under Charles I.

“Even such is time, that takes in trust

Our youth, our joys, our all we have,

And pays us but with earth and dust;

Who, in the dark and silent grave,

When we have wandered all our ways,

Shuts up the story of our days;

But from this earth, this grave, this dust

My God shall raise me up, I trust.”

—Sir Walter Raleigh’s final poem, found in his Bible after execution