Marcus Junius Brutus and the Death of the Roman Republic

Today we examine the life of Brutus on the anniversary of his death, October 23, 42 BC.

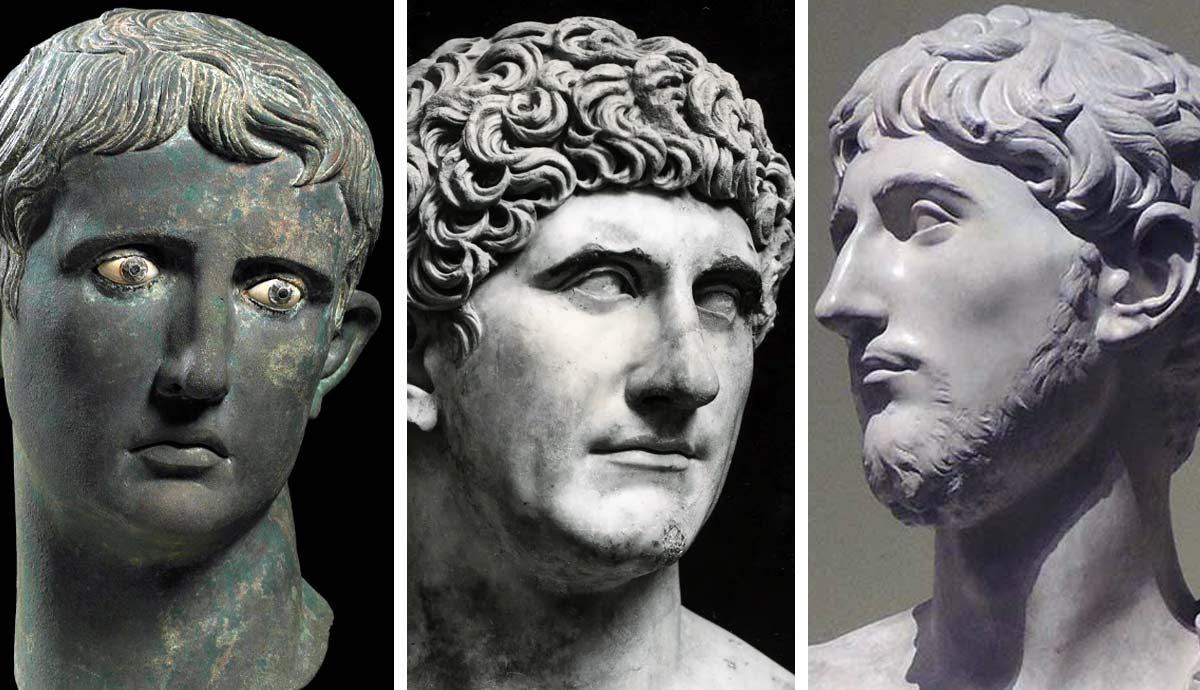

Marcus Junius Brutus stands as one of history’s most complex and controversial figures. He is simultaneously celebrated as the archetypal defender of liberty and condemned as the ultimate traitor. Born around 85 BC into Republican Rome’s most distinguished tyrannicide lineage and dying by his own sword on October 23, 42 BC (precisely 2,067 years ago today), Brutus’s life trajectory from Caesar’s protégé to his assassin to defeated idealist encapsulates the death throes of the Roman Republic itself. Neither the uncomplicated hero of Shakespeare’s imagination nor the demonic traitor of Dante’s Inferno, the historical Brutus emerges as a philosophically committed yet politically naive aristocrat whose well-intentioned actions accelerated the very autocracy he sought to prevent.

The weight of ancestral legacy

The name Brutus carried extraordinary historical freight. Marcus Junius Brutus traced his lineage directly to Lucius Junius Brutus, the semi-legendary founder of the Roman Republic who expelled the last king, Tarquinius Superbus, in 509 BC. According to Roman tradition, that earlier Brutus had feigned stupidity (brutus meaning “dull”) to survive a tyrannical king who had murdered his father and brother, then led the revolution after the rape of Lucretia. He became one of Rome’s first two consuls and demonstrated such devotion to Republican principles that he condemned his own sons to death when they plotted to restore the monarchy. This ancestor’s statue, sword drawn, stood on the Capitoline among those of the kings as a permanent reminder of tyranny’s defeat.

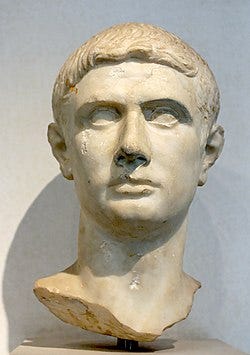

For Marcus Junius Brutus, this heritage was both opportunity and burden. When he served as triumvir monetalis (moneyer) in 54 BC, he issued denarii featuring portraits of both Lucius Junius Brutus and another tyrannicide ancestor, Gaius Servilius Ahala, who had killed the would-be tyrant Spurius Maelius in 439 BC. These coins weren’t mere family vanity; they were political statements advertising Brutus’s credentials as heir to Rome’s tyrannicide tradition.

His father, Marcus Junius Brutus the Elder, served as tribune in 83 BC but was killed by Pompey the Great in 77 BC at Mutina, treacherously executed despite promises of safe conduct. This death when Brutus was approximately eight years old profoundly shaped his upbringing, leaving him in the care of his formidable mother Servilia and creating an initial hatred of Pompey that would eventually be overcome by Republican principle.

Servilia’s shadow and Caesar’s special favor

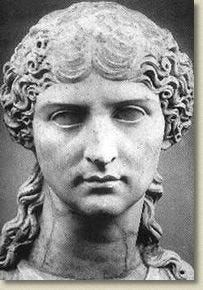

Servilia Caepionis (c. 100 BC to after 42 BC) was among the most powerful women in late Republican Rome, and her influence on her son was decisive. Daughter of a patrician family that traced mythic origins to Romulus, she was half-sister to Cato the Younger, the unbending Stoic who would become Brutus’s primary moral exemplar. After her first husband’s death, she married Decimus Junius Silanus and had three daughters, making the future conspirator Cassius her son-in-law when he married Junia Tertia.

Most significantly for history, Servilia became Julius Caesar’s most famous and enduring mistress. Their affair, lasting approximately 20 years from around 59 BC, became public knowledge in 63 BC during a Senate debate on the Catiline conspiracy when a love note was passed to Caesar. Cato the Younger, suspecting conspiracy, demanded the letter be read aloud. When it proved to be an intimate message from his own half-sister, the humiliated Cato flung it back at Caesar. Suetonius reports that Caesar gave Servilia a black pearl worth six million sesterces, a staggering sum demonstrating his affection. Ancient sources stated Caesar “loved Servilia best of all” his many liaisons.

This relationship spawned speculation, mentioned even by Plutarch, that Caesar might be Brutus’s biological father. However, chronology makes this impossible: Caesar was only 15 years old when Brutus was born in 85 BC. Modern historians universally reject the paternity claim, though the rumor fueled by the later affair persisted in antiquity and shaped how contemporaries interpreted Caesar’s extraordinary favoritism toward Brutus.

After his father’s proscription, Brutus faced legal disability that would have prevented political advancement. Around 59 BC, he was adopted by his maternal uncle Quintus Servilius Caepio, giving him the legal name Quintus Servilius Caepio Brutus, though ancient sources note he “hardly used his legal name,” preferring to emphasize his identity as a Junius Brutus with all its Republican resonance.

Philosophy as formation: Cato’s uncompromising pupil

The single most important influence on Brutus’s character was his uncle Cato the Younger (95 to 46 BC), the most prominent Roman practitioner of Stoic philosophy. After Brutus’s father died, Cato took primary responsibility for raising his nephew, imbuing him with Stoic principles of self-control, virtue, reason, and duty to the Republic above personal interest. Cato modeled that philosophy should be lived, not merely studied; he walked barefoot through Rome, wore only a toga without tunic, lived austerely despite wealth, and demonstrated inflexible moral standards.

In 58 BC, young Brutus served as assistant when Cato governed Cyprus, beginning his practical political education. Throughout the 50s BC, Brutus aligned himself with Cato and the conservative optimates faction, defending Republican institutions against ambitious strongmen.

Brutus’s formal education followed the aristocratic pattern: early training with the grammarian Staberius Eros, then around 60 BC, advanced study in Athens under Pammenes (rhetoric) and multiple philosophers. While exposed to Stoicism, Brutus became particularly influenced by the Academic (Platonic) school under teachers like Theomnestus and Aristos. Plutarch reports the Platonic tradition had an “especially profound influence” on him, emphasizing a duty to restore justice and overthrow tyrants. This philosophical eclecticism, primary moral framework from Stoicism, primary intellectual framework from Platonism, would provide both motivation and justification for his most consequential act.

Brutus wasn’t merely a consumer but producer of philosophy. He wrote treatises on virtue, duties, and patience that ancient sources praised highly. In 52 BC, he wrote De Dictatura Pompei opposing Pompey’s potential dictatorship, and a defense of Milo’s killing of Clodius as justified for Rome’s good. Cicero so admired his intellectual talents that he dedicated two major treatises (Brutus and Orator) to him and cultivated their relationship throughout the 50s BC.

When Cato committed suicide at Utica in 46 BC rather than live under Caesar’s dictatorship, disemboweling himself and, when doctors tried to save him, tearing out his own intestines, it became the ultimate Stoic statement against tyranny. Brutus wrote a laudatory pamphlet entitled Cato eulogizing his uncle. The following year, he divorced his wife Claudia to marry Cato’s daughter Porcia, definitively aligning himself with his uncle’s uncompromising Republican legacy.

Civil war and Caesar’s clemency

When Caesar’s Civil War erupted in January 49 BC, Brutus faced an agonizing choice. Despite Pompey having killed his father, Brutus sided with Pompey against Caesar, a decision demonstrating that Republican principles trumped personal vendetta. Pompey represented the Senate and traditional values; Caesar represented autocratic power threatening the constitution.

The decisive Battle of Pharsalus on August 9, 48 BC in Thessaly saw Pompey’s numerically superior forces routed by Caesar’s veterans. According to Plutarch, Caesar gave specific orders: if Brutus gave himself up voluntarily, take him prisoner without harm; if he persisted in fighting, leave him alone and do him no violence. After the defeat, Brutus fled to Larissa and wrote to Caesar, who “welcomed him graciously” and granted amnesty. This extraordinary pardon was almost certainly influenced by Caesar’s affair with Servilia.

What followed was even more remarkable. Caesar showered Brutus with honors that exceeded those given any other pardoned Pompeian: governorship of Cisalpine Gaul (46 to 45 BC), urban praetorship for 44 BC (the highest position in Rome, chosen over Cassius), and designation for consulship in 41 BC. The special treatment reflected Caesar’s genuine affection for Brutus, shaped by decades of intimacy with Servilia and perhaps seeing in this brilliant young philosopher a kindred spirit.

Yet this relationship was profoundly complicated. Brutus had written praising Cato while carefully also highlighting Caesar’s clementia (clemency). He maintained good relations even after marrying Porcia in June 45 BC. Ancient sources present a man torn between gratitude to Caesar personally and philosophical opposition to autocracy structurally, a tension that would prove fatal to both men.

The conspiracy: philosophy meets family pressure

The conspiracy’s origins remain disputed in ancient sources. Cassius Dio and Appian have Cassius Longinus (Brutus’s brother-in-law) approaching Brutus first; Plutarch suggests Brutus approached Cassius at Porcia’s urging. Most historians believe Cassius was the driving force, the “moving spirit,” while Brutus provided moral legitimacy. A meeting between them on February 22, 44 BC sealed their agreement that something must be done to prevent Caesar from becoming king.

Despite his philosophical principles, Brutus was initially reluctant. He had received enormous favors from Caesar and maintained good personal relations. The conspirators worked to overcome this reluctance through a sustained campaign. By autumn 45 BC, graffiti appeared in Rome glorifying Lucius Junius Brutus and criticizing Caesar’s kingly ambitions. Messages appeared on the praetor’s chair: “You are sleeping, Brutus” and “You are not Brutus.” Derogatory comments in open courts suggested he was failing to live up to his ancestors.

Porcia’s legendary test of her constancy demonstrates the pressures surrounding Brutus. Noticing her husband troubled and suspecting conspiracy, she believed he distrusted her as a woman who might break under torture. To prove herself, she secretly stabbed her own thigh with a barber’s knife, left it untreated for a day, and endured fever and pain. Showing Brutus the wound, she declared: “I, Brutus, being daughter of Cato, was given to you in marriage…to bear part in all your good and evil fortunes.” Ancient sources disagree whether Brutus actually revealed conspiracy details, but Porcia was extremely anxious on the assassination day, sending messengers to check if Brutus lived.

Multiple factors drove Brutus to join: Republican ideals learned from family and Cato; Platonic duty to overthrow tyrants; Stoic commitment to virtue over personal obligation; the weight of ancestral expectation; Caesar’s increasingly monarchical behavior (deposing tribunes, accepting divine honors, becoming “dictator perpetuo”); and the transformation of the Senate into a rubber stamp that blocked traditional political advancement for his generation.

Once committed, Brutus became the symbolic leader. His involvement gave the conspiracy moral legitimacy; as descendant of the founder of the Republic, his participation transformed potential political murder into tyrannicide. Brutus insisted they target only Caesar, rejecting proposals to also kill Mark Antony, arguing that killing Antony would make them appear as mere assassins rather than liberators. This decision would prove disastrous.

The Ides of March: twenty-three wounds

The assassination occurred on March 15, 44 BC at the Curia of Pompey, attached to Pompey’s Theatre, while the regular Senate building underwent renovation. The date held symbolic importance; consuls had traditionally assumed office on the Ides until the mid-2nd century BC. Caesar was scheduled to depart March 18 for military campaigns against the Getae and Parthians, making this the last possible moment. Approximately 60 to 70 conspirators participated.

That morning, Caesar’s wife Calpurnia, disturbed by nightmares of his murder, begged him not to attend. Caesar initially sent Mark Antony to dismiss the Senate. But Decimus Brutus Albinus, one of Caesar’s closest friends, whose betrayal was perhaps most shocking, went to Caesar’s house and convinced him to attend, asking “Will someone of your stature pay attention to a woman’s dreams?”

En route, Caesar encountered the soothsayer Spurinna who had warned him. Caesar called out: “Well, the Ides of March have come!” Spurinna replied: “Aye, the Ides have come, but they are not yet gone.”

Inside, Mark Antony was detained outside by Trebonius. Tillius Cimber approached Caesar presenting a petition to recall his exiled brother. Other conspirators crowded around. Cimber grabbed Caesar’s shoulders and pulled down his toga, the signal. Caesar cried “Why, this is violence!”

Publius Servilius Casca struck first at Caesar’s neck, delivering only a glancing blow to the shoulder. Caesar grabbed Casca’s arm, crying in Latin: “Casca, you villain, what are you doing?” Casca shouted in Greek: “Brother! Help me!” Then Casca’s brother Gaius struck Caesar between the ribs, the only wound later determined to be fatal. The conspirators attacked from all directions: Cassius slashed Caesar’s face, Bucilianus stabbed his back, Decimus sliced his thigh, and Brutus struck Caesar in the groin.

Caesar attempted escape but, blinded by blood, tripped and fell. The conspirators continued stabbing as he lay on the steps, 23 wounds total according to most sources. Caesar fell at the base of Pompey’s statue, a bitter irony.

His last words remain disputed. Suetonius reports Caesar died “uttering not a word,” though some sources claimed he said in Greek “καὶ σύ, τέκνον” (kai su, teknon, “You too, child?”) upon seeing Brutus. The famous Latin phrase “Et tu, Brute?” is Shakespeare’s invention, not historical. The Greek phrase, if spoken, may have been a curse rather than surprise; some classicists interpret it as “You too will have your turn,” a prediction of Brutus’s fate. A physician’s autopsy (the earliest known post-mortem report in history) established that only the second wound was fatal; Caesar died primarily from blood loss. His body lay untouched until nightfall, when three slaves carried him home on a litter, one arm hanging down.

Aftermath: liberation becomes catastrophe

The conspirators marched to the Capitoline Hill expecting celebration. Brutus had prepared a speech celebrating the Republic’s restoration but found silence, not jubilation. Citizens locked themselves in houses as rumors spread. The popular response shocked the conspirators; they had catastrophically misjudged public sentiment.

Before Lepidus’s troops arrived, Brutus spoke at a public assembly, though the text is lost. The assassins promoted democracy and liberty, telling people not to expect harm. But support was tepid at best. On March 17, Mark Antony summoned the Senate to broker a compromise: general amnesty for assassins, but all Caesar’s acts remained valid for two years. Caesar would receive a public funeral. This settlement meant Brutus kept his praetorship and provincial assignment.

March 20, 44 BC: Caesar’s funeral became the turning point. Mark Antony delivered a devastatingly effective oration, reading Senate decrees honoring Caesar, the oath senators had sworn to protect him, and revealing Caesar’s will leaving 75 drachmas to every Roman citizen plus his gardens for public use. A wax effigy displaying all 23 wounds was raised mechanically for all to see. The crowd became enraged. Mobs attacked conspirators’ houses with firebrands. One victim was Cinna the poet, torn to pieces by a crowd confusing him with Cinna the conspirator.

Popular hostility forced Brutus and Cassius to leave Rome in April. Brutus withdrew to his estate at Lanuvium, 20 miles southeast of Rome. The Senate initially offered insulting minor positions (grain-purchasing in Asia for Brutus, Cyrene for Cassius), later assigning them Crete and Cyrene, small, insignificant provinces.

In August 44 BC, Brutus left Italy for Athens, where he was acclaimed and recruited supporters among young Romans studying there, including Cicero’s son. Meanwhile, political chaos in Rome intensified as Antony maneuvered against Caesar’s heir Octavian, setting the stage for renewed civil war.

Eastern campaigns and the gathering storm

Moving with impressive speed, Brutus seized control of Macedonia, Illyricum, and Greece, taking command of Roman legions stationed there; ironically, many were veteran Caesarian troops. Cassius secured 12 legions in Judea and Syria, defeating Dolabella who had killed the conspirator Trebonius.

In January 42 BC, they joined forces at Smyrna in Asia Minor, commanding 19 legions (approximately 80,000 infantry) plus 17,000 to 20,000 cavalry including mounted archers. Their campaign through southern Asia earned Brutus significant criticism. They brutally attacked cities supporting their enemies, particularly at Xanthus where they enslaved populations and plundered wealth. Plutarch presents Brutus regretting the violence with tears, though this was a common literary device. The campaign revealed contradictions in Brutus’s character: philosopher committed to virtue yet capable of extreme violence when necessary.

Brutus plundered Greek cities to build war chests, extracting enormous levies and converting wealth into Roman coins bearing his own portrait following Caesar’s example. He addressed soldier loyalty concerns (many were former Caesarian veterans) with speeches and substantial bonuses: 1,500 denarii per legionary, 7,500 per centurion.

Meanwhile in Rome, catastrophic developments sealed the conspirators’ fate. After the War of Mutina, Octavian, Mark Antony, and Lepidus formed the Second Triumvirate on November 27, 43 BC with extraordinary legal powers. Their first act instituted brutal proscriptions targeting political enemies: around 300 senators and 2,000 equites condemned. Cicero was executed on December 7, 43 BC, his head and hands nailed to the Forum speaker’s platform. Decimus Brutus was executed in Gaul. The triumvirs confiscated properties to finance war, declaring vengeance for Caesar’s death.

Philippi: the Republic’s suicide

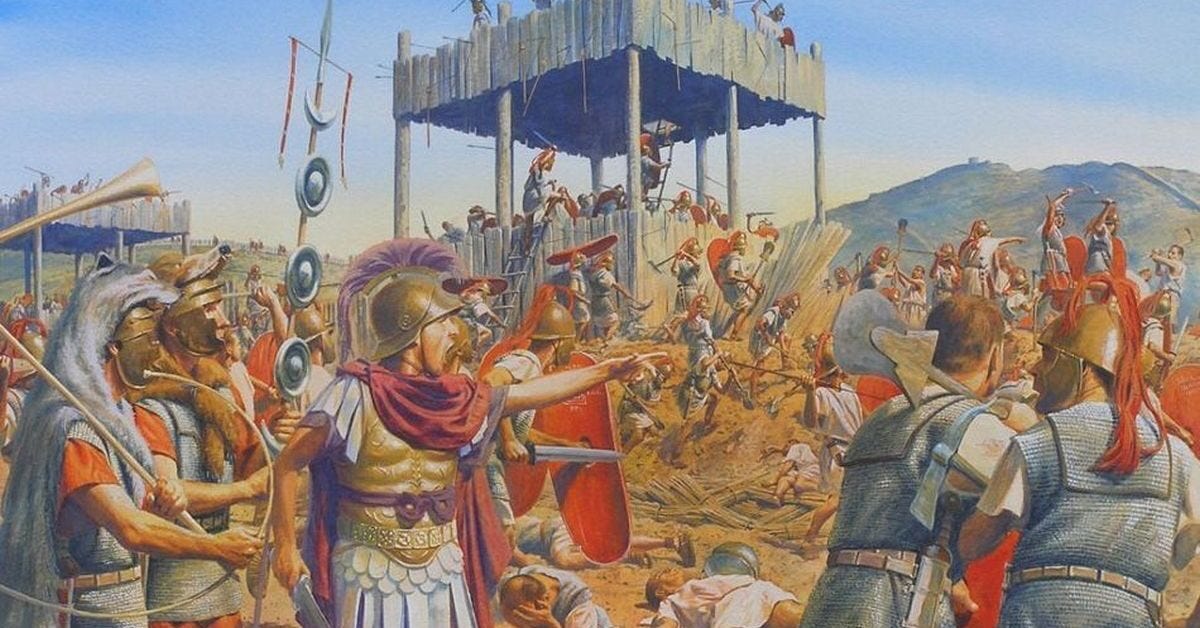

In September 42 BC, Brutus and Cassius occupied superior defensive positions near Philippi in Macedonia. Brutus positioned his camp north of the Via Egnatia on high ground; Cassius held the south. Their position was anchored by marshes and mountains, fortified with ramparts and ditches. They controlled naval superiority and easy supply access via Neapolis (modern Kavala). The Liberators did not want decisive battle, preferring to hold defensive positions and use naval superiority to starve out enemies.

Antony and Octavian arrived with 28 legions (approximately 40,000 to 50,000 infantry, 13,000 cavalry); Octavian delayed at Dyrrachium due to illness. The triumvirs were in precarious position: depleted regions could barely supply their army, while the Liberators had the tactical advantage. They needed to force engagement despite inferior positioning.

First Battle of Philippi, October 3, 42 BC: For weeks Antony attempted to lure the Liberators from positions. He then secretly cut a causeway through southern marshes to outflank Cassius. When Cassius discovered this, he built a transverse wall to cut off the advance. On October 3, this standoff triggered general engagement. Antony ordered full assault on Cassius’s fortifications. Simultaneously, Brutus’s soldiers, provoked without waiting for orders, charged Octavian’s forces.

On the northern wing, Brutus achieved complete victory. His forces routed Octavian’s troops, captured his camp, seized standards of three legions, a clear sign of total defeat. Octavian himself was not found in his tent; sources report he hid in the marsh. His forces suffered approximately 16,000 casualties.

On the southern wing, Antony broke through, demolished Cassius’s palisade, and captured his camp. Cassius lost about 8,000 men. The battlefield was vast; dust made assessment impossible. From a hilltop, Cassius couldn’t see Brutus’s victory. Receiving false reports that Brutus had also been defeated, Cassius ordered his freedman Pindarus to kill him. Brutus mourned over his body, calling him “the last of the Romans,” avoiding public funeral to prevent morale damage.

The battle was essentially a draw; each side won on one wing. However, the loss of Cassius, the better military strategist, was catastrophic. That same day, the Republican fleet destroyed triumvir reinforcements, two legions plus supplies, worsening the triumvirs’ strategic position, though Brutus apparently never received this news.

Second Battle of Philippi, October 23, 42 BC: For three weeks, Brutus maintained defensive strategy. He assumed command of Cassius’s forces, promising rewards (1,000 denarii per soldier). However, mounting pressures forced his hand: officers and soldiers demanded action; eastern allies began deserting; most critically, Antony’s maneuvers threatened to cut supply routes to Neapolis, which would isolate him and force starvation or hazardous retreat. Brutus had to extend his lines southward, stretching forces dangerously thin. As he later said: “I seem to carry on war like Pompey the Great, not so much commanding as commanded.”

Brutus abandoned better judgment and offered battle on the afternoon of October 23. The armies engaged in brutal close combat. Cassius Dio reports they “did not resort to usual manoeuvres” but immediately advanced to sword combat. Initially, Brutus’s forces pressed hard, but his eastern flank was fatally weak, stretched too thin from extending the line. The triumvirs broke through the weak center and swung left to take Brutus in flank and rear. His legions were driven back slowly, then rapidly as ranks crumbled. Octavian’s forces captured camp gates before the routing army could reach safety. The Republican army couldn’t reform. The triumvirs’ victory was complete.

Death of the last Republican: October 23, 42 BC

Brutus retreated into nearby hills with approximately 14,000 men from his original force. Seeing surrender and capture inevitable, he decided on suicide. He asked several followers to assist: Clitus, Dardanius, Volumnius; all refused.

Before dying, Brutus spoke of Caesar’s ghost, which had appeared twice: once at Sardis and again the previous night at Philippi. He told Volumnius: “The ghost of Caesar hath appeared to me two several times by night, at Sardis once, and this last night here in Philippi fields. I know my hour is come.”

Finally, a soldier named Strato agreed to assist. Brutus’s last words varied across sources. According to Plutarch: “By all means must we fly, but with our hands, not our feet.” He also uttered a verse from Euripides’ Medea: “O Zeus, do not forget who has caused all these woes.” According to Cassius Dio: “O wretched Virtue, thou wert but a name, and yet I worshipped thee as real indeed; but now, it seems, thou were but fortune’s slave.”

Strato held Brutus’s sword while Brutus ran upon it, dying by his own hand on October 23, 42 BC, at approximately age 43, exactly 1,983 years ago today.

Plutarch reports Mark Antony treated Brutus’s body with honor, covering his corpse with his own purple cloak. Antony remembered that Brutus had stipulated, as condition for joining the conspiracy, that Antony’s life be spared. He gave Brutus honorable burial, treating him with respect due a Roman noble. However, Suetonius claims Octavian had Brutus’s head cut off to display before Caesar’s statue, though it was later lost in an Adriatic storm.

The contested legacy: from Satan’s jaws to noblest Roman

Ancient perspectives diverged sharply. Cicero and Republican sympathizers admired Brutus as principled defender of liberty. Plutarch assessed that “Brutus was the only man to have slain Caesar because he was driven by the splendour and nobility of the deed, while the rest conspired against the man because they hated and envied him.” Even Antony at the burial praised him as having acted from “splendour and nobility.” Tacitus noted Brutus “laid bare convictions of heart frankly and ingeniously.”

Conversely, Caesarian propagandists portrayed him as ungrateful traitor. The main charge was ingratitude: Caesar pardoned, promoted, and enriched him, yet Brutus betrayed this clemency with violence. Augustus claimed: “I sent into exile the murderers of my father, punishing their crimes with lawful tribunals; and afterwards, when they made war upon the Republic, I twice defeated them in battle.” Under emperors, admiration for Brutus was interpreted as protest against the imperial system. Cremutius Cordus was charged with treason under Tiberius for writing pro-Brutus history.

Dante’s Inferno (c. 1320) placed Brutus in the absolute lowest circle of Hell, the Ninth Circle (Cocytus) reserved for traitors. Along with Cassius and Judas Iscariot, Brutus is eternally tortured in one of Satan’s three mouths, receiving the worst punishment in Dante’s Hell. The theological justification: killing Caesar meant resisting God’s “historical design,” as the Roman Empire was divinely ordained to bring Christianity. Caesar represented legitimate authority; assassination was betrayal of God’s plan, comparable to Judas’s betrayal of Christ.

The Renaissance dramatically reversed this judgment. Humanists viewed Brutus positively as defender of republican ideology. The assassination symbolized resistance to tyranny. Renaissance city-states identifying with the Roman Republic adopted Brutus as symbol of civic virtue. Michelangelo’s Brutus bust (1539 to 1540), his last commissioned sculpture, created after the defeat of the Republic of Florence, shows heroic aspect with “strength of will” and “cold tranquility” mixed with “hatred, wrath and bitter contempt.” Historical “Brutuses” appeared: Lorenzino de’ Medici killed Duke Alessandro in 1537; the anti-monarchist tract Vindiciae contra tyrannos (1579) was published under pseudonym “Stephanus Junius Brutus.”

Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar (1599) crystallized the most enduring image. Despite the title, Brutus is the protagonist and moral center. Drawing on Plutarch via Thomas North’s translation, Shakespeare presents him as tragic hero: rigid idealist whose honor is simultaneously greatest virtue and deadly flaw. He’s philosophically consistent but politically naive, wants the assassination to appear noble, and is torn between loyalty to Caesar and duty to Rome.

Antony’s famous eulogy encapsulates this interpretation: “This was the noblest Roman of them all. All the conspirators save only he Did that they did in envy of great Caesar; He only, in a general honest thought And common good to all, made one of them…This was a man!” Shakespeare’s invention of Caesar’s last words, “Et tu, Brute?”, entered common language and forever shaped popular understanding. This portrayal became the dominant lens through which subsequent centuries viewed Brutus.

Modern historical assessments emphasize complexity. Kathryn Tempest’s comprehensive 2017 biography Brutus: The Noble Conspirator “recognizes complexity of his personality and actions”: high-minded and just, but also dubious finances (48% interest rates in Salamis) and brutal subjection of eastern cities. Ronald Syme argued: “To judge Brutus because he failed is simply to judge from the results.” Many historians believe the Republic was unsalvageable by 44 BC after a century of civil wars; Caesar’s dictatorship was symptom, not cause, of constitutional collapse.

Conclusion: The philosopher who misjudged history

Marcus Junius Brutus embodied the contradictions of late Republican Rome: philosophically trained yet financially rapacious, personally close to Caesar yet opposed to autocracy, admired for integrity yet capable of cruelty, intellectually brilliant yet politically catastrophic. He was neither Shakespeare’s idealized tragic hero nor Dante’s demonic traitor, but rather an aristocrat genuinely committed to Republican principles who catastrophically misjudged both political reality and human nature.

His formation (legendary tyrannicide lineage, Cato’s Stoic tutelage, Platonic education emphasizing duty against tyrants, the weight of family expectation) created a man philosophically compelled to resist Caesar’s monarchy. Yet his assassination achieved the opposite of its intention. Rather than restoring the Republic, it triggered renewed civil war, the Second Triumvirate’s proscriptions killing thousands including Cicero, and ultimately the permanent establishment of the very autocracy he sought to prevent under Augustus.

The fundamental tragedy was not moral failure but historical obsolescence. Brutus fought for a world that no longer existed: the competitive, oligarchic Republic of balanced institutions and senatorial authority. A century of civil wars, military strongmen, and social transformation had made that system unsustainable. Brutus’s Platonic duty to overthrow tyrants and his family’s Republican traditions were artifacts of an earlier age, inadequate to navigate the political realities of 44 BC.

His death on October 23, 42 BC at Philippi marked not just a personal end but a constitutional one. With the defeat of Brutus and Cassius, the last significant defenders of the old Republic died. As one historian observed, “the Roman Republic committed suicide at Philippi.” The ghost Caesar supposedly promised Brutus would see him at Philippi proved prophetic, not as supernatural apparition but as historical inevitability. Caesar’s autocracy would be vindicated not by Caesar himself but by his adopted heir Octavian, who learned from both Caesar’s success and Brutus’s failure to create the Principate.

Each generation has reinterpreted Brutus through its own lens: medieval Christians saw divine traitor, Renaissance republicans saw liberty’s champion, Enlightenment philosophers debated tyrannicide’s morality, modern historians see tragic complexity. This contested legacy reflects ongoing tensions between liberty and order, principle and pragmatism, revolutionary idealism and conservative stability. The name Brutus remains simultaneously synonymous with principled resistance to tyranny and with betrayal itself, “brute” ingratitude repaying benevolence with violence.

Perhaps the final assessment belongs to Brutus himself. His last words according to Cassius Dio captured the disillusionment of a philosopher confronting reality’s refusal to conform to principle: “O wretched Virtue, thou wert but a name, and yet I worshipped thee as real indeed; but now, it seems, thou were but fortune’s slave.”

The man who lived by Stoic and Platonic ideals died recognizing that virtue alone could not overcome historical forces, that philosophical duty could not restore a Republic whose time had passed, and that good intentions anchored in outdated assumptions could accelerate the very outcomes they sought to prevent. In this recognition lies both Brutus’s tragedy and his enduring significance: as cautionary example of idealism untempered by realism, principle unbounded by prudence, and the dangerous conviction that violence in liberty’s name can restore what time and circumstance have already destroyed.